Posted 3 years ago in Trending, Guest Blog by Blair Kamin: author of “Who Is the City For?"

10 MIN READ – Nearly 152 years ago, with the ground still hot from the Great Chicago Fire and the core of his city in ruins, Joseph Medill, the late, great former editor of the Chicago Tribune, published a prophetic editorial.

“Cheer Up,” the headline read. And there was this memorable line in the text: “Chicago Shall Rise Again.”

My message echoes Medill’s: “Downtown Chicago Shall Rise Again.”

Skeptics will scoff: What about the 20 percent office vacancy rate? What about North Michigan Avenue’s 30 percent retail vacancy rate? And the challenge posed by the shift to remote work is unprecedented.

To which I reply: So what?

The Great Fire posed an unprecedented challenge. So did the postwar flight to suburbia. So did the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, which had false prophets predicting that no one would want to work in Willis Tower.

Downtown has overcome all these hurdles. And it has the capacity to overcome the ones it faces today, though reimposing a suburban head tax and making the hotel-motel tax even higher won’t make things any easier.

Cloud Gate in Millennium Park. Photo by Lee Bey.

If you scan the news about downtown, you can see optimistic signs that resemble fresh blades of grass popping through late-winter snow:

--More than 2.5 million people are expected to attend conventions at McCormick Place this year, up from 1.5 million last year. That will boost downtown hotels and the ridesharing business.

--Far from being hammered by the pandemic, the Loop’s population has grown. It now stands at 46,000, a 9 percent increase over 2020.

--In late January, office occupancy levels in Chicago topped 50 percent for the first time since the pandemic shutdowns. And, as Michael Edwards has told me, Loop theaters are packing in the crowds.

Despite the bleak short-term picture, then, the real question is not whether downtown will bounce back, but when and how?

Should the next mayor and downtown interests like the Chicago Loop Alliance seek to restore downtown to the way it was before Covid-19 hit? Or should you seek to build a better, more equitable version of downtown?

I’m going to argue for a more equitable downtown. I’m going to give you six ideas for how to achieve revival. And at the risk of entering the political fray, I’m going to add this: Equity still matters even though Lori Lightfoot lost her re-election bid. Chicago can’t be a world-class city if it’s a tale of two cities.

What do we mean by “equity”? In my new book, “Who Is the City For?”, I articulate a double meaning of the word.

First, equity means fair treatment for people and neighborhoods that historically have suffered from discrimination and disinvestment.

Second, equity means the devotion of attention and resources to the public spaces that we share, from sidewalks and streets to transit stations and parks.

Think of Millennium Park. Think of the downtown Riverwalk. Think of the hundreds of thousands of visitors they’ve drawn and the hundreds of millions of dollars in investment that they’ve sparked.

When I’m talking about downtown equity, then, I don’t just mean opening access to a downtown whose residents are largely white and affluent.

I also mean strategically upgrading downtown’s public spaces to speed its transition to a modern mixed-use district from an old-school central business district—a CBD. (Which is not to be confused with the ingredient they put in the gummies you buy at the weed shop.)

Despite the recent increase in the number of downtown residents—as of 2019, nearly 229,000 people lived in the area roughly bounded by the Stevenson Expressway on the south, Lake Michigan on the east, North Avenue on the north and Ashland Avenue on the west--downtown streets still feel empty, or, at best, half-empty. And the stakes of that emptiness aren’t just about the appearance of vitality. They’re about the bottom line--property values. The central area accounts for roughly 40 percent of Chicago’s tax base.

Which brings us to this nightmare scenario: A downward spiral in which downtown remains awash in vacant office space, building values plummet, the city is strapped for cash, its ability to provide services withers, and things deteriorate to the point where decades of downtown growth are undone.

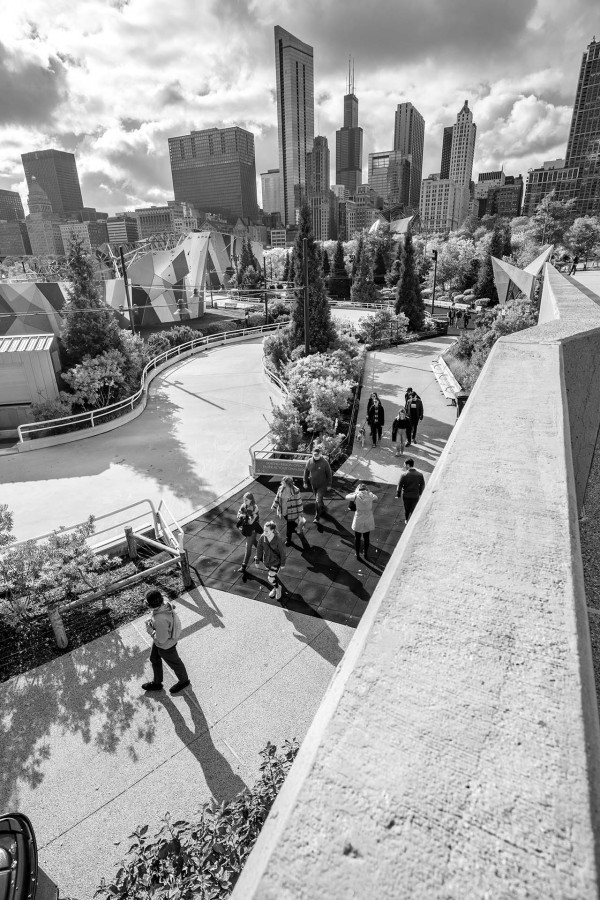

Maggie Daley Park. Photo by Lee Bey.

So what is to do be done? Here are six ideas:

First, plan, don’t panic.

When you panic, you make desperate, stupid decisions. You glom on to the urban design flavor-of-the-month and ignore the fundamental dynamics that make cities work. Think of the long-gone, late-1970s transit mall on State Street. In those days, trying to compete with suburban malls, urban retail strips foolishly tried to become suburban themselves, banishing cars and turning sidewalks into wide-open spaces. It ended, as the Tribune once wrote, in failure and bus fumes.

I urge you to remember that mistake. And learn from the smart planning that Chicago did in the 1990s to turn State Street into separate but complementary zones—a theater and entertainment district on the north, a retail zone in the middle, and a cultural and education area to the south. Significantly, the zones put people on the street at different times of day and fed foot traffic from one area to another. The 1996 renovation that got rid of the transit mall and restored a traditional streetscape could not have succeeded without these moves.

The lesson: Confident downtowns do not panic. They follow in the tradition of Daniel Burnham. They plan. They make big plans, Burnham style. And they make small plans, which wisely recognize that different streets, and even different sections of streets, represent different but interrelated parts of a larger urban ecosystem.

Point two: Plans need an overall direction. Here’s a promising one for downtown—a shift toward CSD from CBD.

As downtowns across America struggle to revitalize, cutting-edge urban thinkers are talking up a new concept--the CSD, short for “central social district.”

What, you ask, is a CSD? It consists, as economic development expert N. David Milder has said, of downtown functions and venues that meet our collective and individual social needs. Think museums, art galleries, restaurants, parks, plazas, and housing. That’s very different from the core commercial functions of the CBD—offices and shopping.

The big potential upside of CSDs is their ability to attract and keep people downtown. The CSD does not replace the CBD. It complements the CBD. Restaurants and cultural attractions make nearby office buildings more desirable—and thus more valuable.

To be sure, downtown Chicago already has a lot of aspects of a central social district. It’s been building housing since Marina City in the 1960s. And it’s already got the Art Institute and Millennium Park. But as I mentioned earlier, all those features are not producing enough activity to make up for the drop in office-related foot traffic. To promote vitality, downtown needs to push the needle further in the direction of the CSD.

How to do that is the subject of point three: Capitalize on the severe downturn in the office market to make downtown more residential.

It’s possible, of course, that remote work will fall from favor as people miss water-cooler talk and organizations realize that face-to-face contact is the best way to build team spirit. But it’s also possible that remote work is here to stay.

Fine.

So be like Rahm--don’t let a serious crisis go to waste.

That’s what Lightfoot and her planning commissioner, Maurice Cox, have been doing on LaSalle Street. They’re using TIF subsidies to entice developers to create new housing, including affordable housing, in handsome old office buildings.

Some in the business community bristled at this mandate, but, as the Sun-Times recently reported, developers have now proposed more than $1 billion in plans for seven sites on or near LaSalle.

The lesson: The stick of affordable housing requirements can work when it’s combined with the carrot of TIF subsidies.

The broader lesson: Whoever the next mayor turns out to be, we should not backslide on building more affordable housing. For the import of more downtown housing promises to reverberate citywide.

Not only would it allow middle-class people--paralegals as well as lawyers, nurses as well as doctors--to live downtown. By expanding housing supply to meet demand, it would address the citywide affordable housing shortage, which constrains urban growth, pushes up property taxes and forces longtime residents out of their neighborhoods. And, of course, more affordable housing would save energy by allowing people to walk to jobs, shops, and entertainment.

Point four: To lure more people to live downtown, continue to upgrade the public realm.

Putting sidewalk cafes on LaSalle Street will signal that the street is now open to the Starbucks crowd. But that’s the easy part. In reality, the private sector can only do so much to change the public realm.

The public sector has to be responsible for the big moves, like new infrastructure that will enable downtown to take on more characteristics of a CSD, especially parks and open spaces.

So the next mayor should pick up on the conceptual plans done for Rahm Emanuel. Extend the downtown riverwalk along the Chicago River’s south branch all the way to Chinatown and its beautiful riverfront parks. And while you’re at it, increase the number of curb-protected bike lanes downtown.

If you want people to live downtown, you’ve got to make it more livable, less formal—in short, take the old-fashioned starch out of its collar.

Point five: Build short-term momentum.

Big plans like the ones I’ve been talking about take years to accomplish. But right now, downtown Chicago could use some short-term excitement to kick-start its revival and persuade people that downtown is safe.

The conventional wisdom on public safety, one you’ve heard during the mayoral campaign, is to put more cops on the street. But there’s another way, based on the brilliant 1980 analysis of small urban spaces in Manhattan by William H. Whyte. Among Whyte’s insights: The presence of people attracts more people. People feel safer, less conspicuous, in crowds. Crowds, in short, can do as much as cops to make people feel sale.

So how to bring crowds back?

I would try every trick in the book, especially piggybacking on existing events that draw thousands of people downtown.

Think of Open House Chicago, the Chicago Architecture Center program that gives people free access to great interior spaces. Now think of what it could do for LaSalle Street. In Chicago, there is no greater ensemble of interiors than the one on LaSalle.

They range from the greenhouse-like splendor of the Rookery Building’s light court to the Roman Revival majesty of the Wintrust Grand Banking Hall to the Chicago Board of Trade’s dazzling Art Deco lobby.

231 S. LaSalle Street (The Central Standard Building). Photo by Lee Bey.

The lesson: Build on the success of your placemaking Sundays on State program and seize upon every opportunity you can to bring and keep people downtown.

My sixth and final point echoes what I said earlier about equity. Don’t backslide.

Downtown is not an island, and its revival can’t happen in a vacuum. It is, in fact, deeply inter-connected with what happens in the rest of Chicago.

In the theater there’s an expression: The show starts on the sidewalk. When you see the marquee and stand beneath it, you’re in a transition zone that anticipates the thrill of entering an exotic movie palace.

The same thing applies to downtown, except that your show—the downtown experience—starts (God forbid) at the CTA or Metra station where the commuter begins his or her journey into downtown.

If the commuter has to wait forever for a train, can’t take a seat because it’s occupied by a homeless person, or gets robbed, then you’re running the race to revive downtown with a ten-pound ball on your foot.

I know you cannot snap your fingers and solve the labor shortages that are contributing to CTA’s problems. But you most assuredly can pressure the next mayor to put the heat on the CTA to return its now-desultory service to acceptable levels.

Without safe, clean, reliable, public transit, it is going to be doubly hard to get remote workers to come back downtown.

CTA's Washington/Wabash station. Photo by Lee Bey.

For as we’ve seen in the last few years, the problems of struggling neighborhoods on the South and West Sides invariably will spread into downtown and the North Side.

It is possible, sadly, to build two cities within the borders of a single municipality. But it is impossible to build a wall between them.

To sum up, reviving downtown Chicago should be high on the next mayor’s agenda. Downtown, as your organization is fond of saying, is “everyone’s neighborhood.” It is crucial—financially and spiritually--to the future of all of Chicago.

To bring it back, you need to plan, not panic; accelerate the transition toward CSD from CBD; continue the shift from office to housing; build parks and public spaces that accommodate housing; add short-term razzle-dazzle that brings back the crowds; and remember that the fate of downtown is inseparable from the fate of the neighborhoods. Equity still matters.

As Ben Franklin famously said at the signing of the Declaration of Independence: “We Must All Hang Together, or Most Assuredly, We Will All Hang Separately.”

Or, as Joseph Medill might have said if he were standing here today: “Cheer Up. Downtown Chicago Shall Rise Again.”

If there are any doubters, I’ll be happy to take bets on the downtown revival when the temporary casino opens at Medinah Temple.

Blair Kamin, the former architecture critic of the Chicago Tribune, and Pulitzer Prize winner, is the author of “Who Is the City For? Architecture, Equity, and the Public Realm,” published by the University of Chicago Press. This is a condensed, edited version of a keynote speech he gave to Chicago Loop Alliance’s annual meeting on March 2, 2023.